-

#518 – The Adventures of Electronic (1979)

The Adventures of Electronic (1979)

Film review #518

Director: Konstantin Bromberg

SYNOPSIS: Professor Gromov has constructed a life-like robot boy named Electronic, based on the image of a schoolboy named Sergey. Electronic has the dream of becoming a real human boy, and when the Professor forbids him from interacting with the outside world, he escapes and runs into his double. Sergey has the idea of having them swap places, using Electronic’s super intelligence and strength to excel at school. meanwhile a criminal gang is spying on Electronic, with the aim of kidnapping him to use in a series of high-value heists…

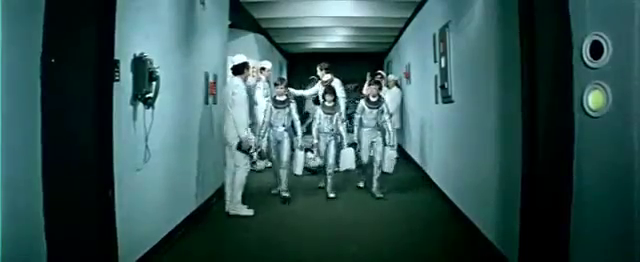

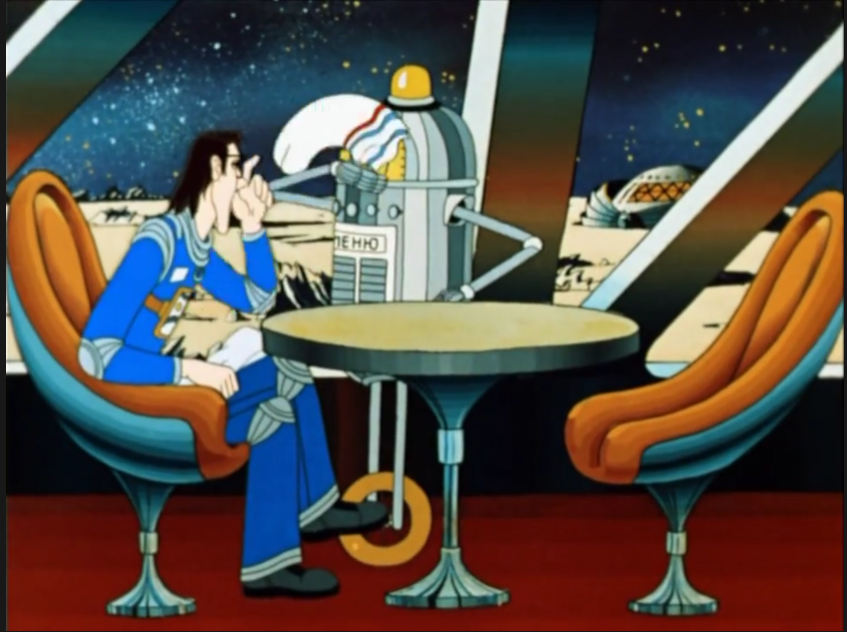

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: The Adventures of Electronic is a 1979 three-part miniseries from the Soviet union. The story starts off introducing Electronic, a boy who is a robot created by Professsor Gromov to look human, and Sergey the human boy who Electronic’s appearance copies (who appeared on a magazine cover). The two eventually run into each other, and have the idea to swap places, so that Electronic can excel in Sergey’s classes at school, and Electronic is given the chance to live as a human; and naturally, hijinks ensue. The story is fairly obviously a combination of Pinocchio and The Parent Trap, although I’m not sure how accessible either of these were available in the Soviet union in 1979. Nevertheless, the story is simple to follow, and paces itself fairly well, with different things going on across the three different episodes of the series. Being aimed at children, there’s very mild threats and danger, but it’s pretty harmless. The series focuses more on humour, adventure, and the occasional musical number, and I imagine it would have been a fun and entertaining adventure for kids at the time. The story doesn’t really explore the range of potential of it’s set up, and often feels like a re-tread of the aforementioned Pinocchio and The Parent Trap, but you don’t really need to be groundbreaking for these types of films/series. The pacing is pretty solid, the characters develop at an even pace throughout, and there’s new elements added in as it goes along to maintain interest, so it does everything it needs to.

While Sergey and Electronic are up to their shenanigans, an international crime ring has been spying on Professor Gromov and, learning of Electronic’s existence, their boss plans to kidnap him to use his abilities to pull off a huge heist. As mentioned, the villains and danger isn’t too threatening as the series is made for kids, but it adds a little excitement to things. Apart from Sergey and Electronic (played by actual twins, but their voices are dubbed by different people), the rest of the cast play a minor role, but their appearance keep scenes energetic and busy, such as the gang of kids that Sergey and Electronic hang about with, the various teachers, and even a dog that joins the kids eventually. The familiar scenes of the school and the kid’s clubhouse also root the film in a very particular setting that the cast’s adventures revolve around, and makes a nice core along with the characters that interacts with the changing elements of the story, creating a nice balance.

The series was apparently very popular when it was released, and I think it’s easy to see why: it follows some tried-and-tested formulas story-wise, and also it’s produced fairly well, with solid camerawork and performances all round. It’s difficult to find too much wrong with it, since it’s aimed at a younger audience and is not intending to be groundbreaking. Overall, The Adventures of Electronic is an entertaining watch that hits the right notes, but is definitely something that would not stand the test of time, being firmly rooted in the time and place it was filmed. Some elements of the story are fairly timeless, but nothing original is added to make it worth a contemporary viewing.

-

#503 – The Mystery of the Third Planet (1981)

The Mystery of the Third Planet (1981)

Film review #503

Director: Roman Kachanov

SYNOPSIS: Captain Seleznyov and his daughter Alice are travelling in their spaceship to other planets to find animals for their zoo. Seleznyov runs into his old friend Gromozeka, who directs them to the Planet of Two Captains, and a museum dedicated to Captains Kim and Buran, who travelled across the universe in their own spaceship. However, they soon become embroiled in a mystery surrounding the museum’s director, and encounter danger as they try and get to the truth…

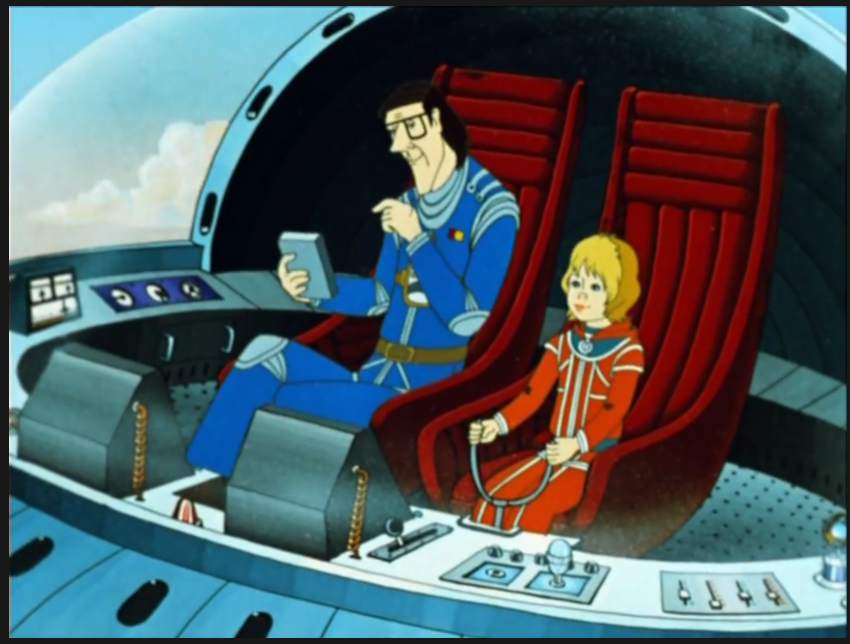

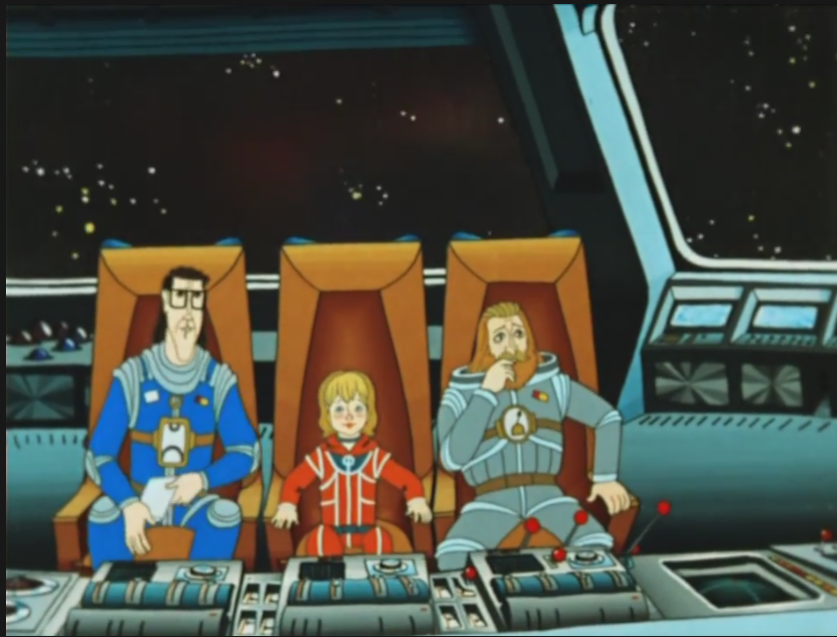

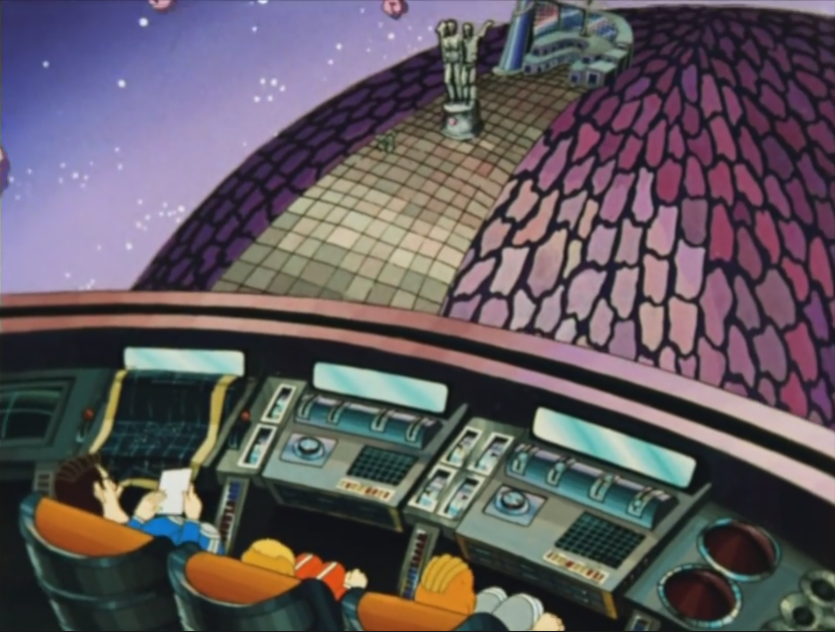

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: The Mystery of the Third Planet is a 1981 animated film. The film is set in the 22nd century, where we see professor Seleznyov and his daughter Alice looking for rare animals for their zoo in Moscow. On the moon, they run into Seleznyov’s friend Gromozeka, who suggests they head to the “Planet of the two Captains,” where a museum dedicated to Captain’s Kim and Buran, who travelled the universe in their spaceship, is located, and may have information about any rare or exotic animals. The story of the film embroils Alice and her Father in a mystery surrounding the fate of the Captain’s and the museum’s director Verkhovtsev. The film has a fairly short runtime at just under fifty minutes, but it fits a lot into a plot that feels complete and full of development and direction, and a mystery to unravel. It is a film primarily aimed at children, so it has to be interesting enough to keep their attention, and it certainly has plenty going on to do that. The world that it creates in the 22nd century is full of futuristic technology, high contrast colours, and weird aliens that sets up a range of interesting scenarios, but the constant moving around from planet to planet can be a bit confusing. When you’re a kid though, you’re not overly concerned about the intricacies of the plot, but rather the energy and excitement that it provides, and there’s some high stakes and danger that does that, so overall it leaves a positive impression.

The film is based on a series of books centred around the main character Alice Selznyov, which were popular in the Soviet Union with children. Alice provides a relatable character for young viewers, and is full of energy and life to fit that role. One of the highlights of the film is the alien designs: being an animated film, it has the creative scope to go wild with the alien designs, which it certainly does. Gromozeka, with his six arms and disturbing pointy eyes is the one that stands out, and is also in keeping with his appearance as described in the books. The live-action adaptations, such as the miniseries Guest from the Future and the 1987 film Lilac Ball didn’t have the budget to bring these creative designs to life, and opted for more humanoid appearances for the aliens, which is a shame. Even the human characters are distinct enough in appearance and design so that they are instantly recognisable, and despite being all different heights and sizes, they still interact seamlessly.

This film was very popular upon it’s release in 1981, and seems to have remained a favourite memory of people who grew up in that era. So much so that the 2009 film Alice’s Birthday, based on another of Alice’s adventures, has a similar art style and direction that I think tries to ride on the nostalgia of this film. It wasn’t just in the Soviet Union either: it was translated and released in the U.S. (twice) and lots of European countries too. Perhaps the runtime makes it fit neatly into a one hour TV slot (including adverts), so that might be a reason. The English dub is very much of the time and is a bit poorly produced, so if you’re going to watch this film, definitely go for the original version with subtitles. Nostalgia certainly plays a part in how fondly this film is remembered, but that’s not it entirely. It definitely does have plenty of good points independent of said nostalgia: it’s packed and energetic plot, it’s creative character designs, and it’s colourful, abstract scenery are fun and will keep the target audience entertained for its runtime. It holds up as a good film in terms of its structure, style, and design, but I’m not sure there’s enough of a spectacle compared to more modern films for younger generations to have that same feeling.

-

#501 – Lilac Ball (1987)

Lilac Ball (1987)

Film review #501

Director: Pavel Arsenov

SYNOPSIS: Travelling aboard their spaceship Pegasus, Professor Selznyova, his daughter Alisa and the rest of the crew encounter Selznyova’s old friend Gromozeka. He explains that he has come from a planet where the population has just been wiped out by a virus that has lain dormant for 26,000 years. The problem is that the same virus was also left on earth, and will activate and wipe out the population in a matter of days unless a cure can be found…

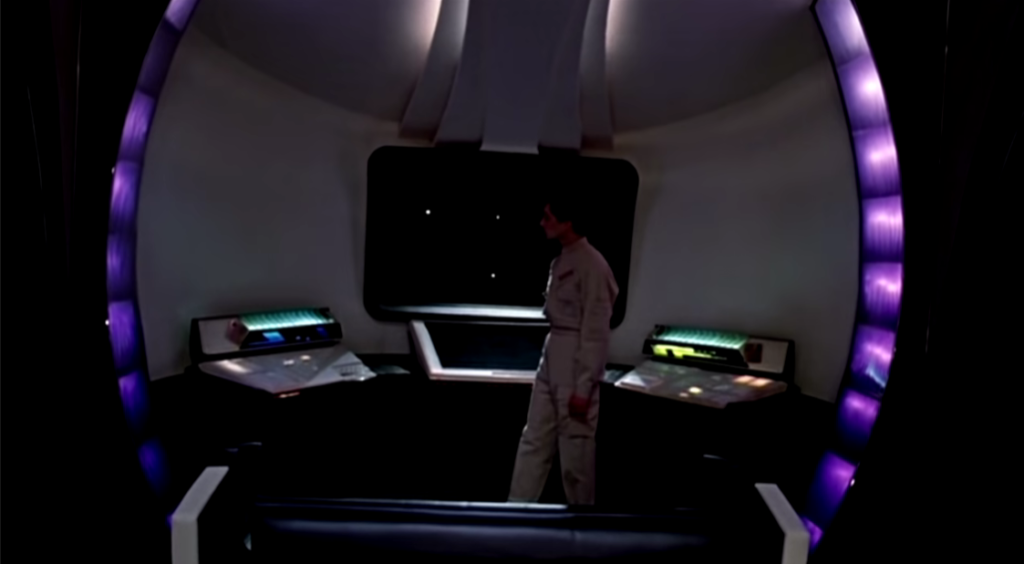

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Lilac Ball is a 1987 children’s sci-fi film based on the novel by Kir Bulychyov. The story starts out aboard the spaceship Pegasus, manned by Professor Selznyova and his crew, including his daughter Alisa. On their travels, they come across the Professor’s friend Gromozeka, who tells them that a 26,000 year old dormant virus has just awakened and wiped out the entire population of a planet…and the same virus is on Earth and will activate in a few days time unless a cure can be found. The only solution is to send Alisa back in time to Earth 26,000 years ago to find the source of the virus. The most notable thing about the film is that it is pretty much an even split between science-fiction and fantasy: almost exactly at the halfway point, the spaceship and future gives way to an ancient Earth filled with fantasy creatures. With a runtime of seventy three minutes, the film certainly packs in a lot of stuff, combining that familiar soviet-era sci-fi aesthetic with some more offbeat fantasy creations. As a film aimed at children, it has to keep up a certain energy level to keep it entertaining, and I think it has plenty of imagination and variety to keep things interesting. The plot is quite packed as mentioned, and is a bit overwhelming to follow. Part of that might be the loose subtitles I watched the film with, and part of it is probably due to the fact that a lot of the original novel was cut to fit it into this fairly short runtime. Intricacies within the plot aren’t too problematic with children’s films though, as long as there’s plenty of jumping off points to spark their imaginations, which I think this film has.

Alisa is the main character of the film, and had appeared in the TV series Guest from the Future in 1984 before this film was made (and portrayed by the same actress). I believe that there is also a series of novels centred around her character, so she’s fairly well established, and it is refreshing to see a good female lead in these types of films. The rest of the characters serve a supporting role, and are a colourful bunch, again split between the more grounded characters in the sci-fi setting, and the fantasy half, where the characters are a bit more outlandish. The earth of 26,000 years ago is probably not very accurate, as there are talking birds, flying monsters, people in wooden houses and other such things which I do not think are historically accurate.

As mentioned, the sci-fi aesthetic feels very familiar if you have watched any other soviet-era sci-fi. The spaceship’s corridors and control panels have that typical look and feel of the time, but have a lot of detail and attention in them that is visually appealing. The spaceship itself is quite a unique design: it is a disc shape with retractable “sails” that resemble paper fans. The scenes with the spaceship flying around evading capture from this giant net…ship…thing is quite well done. I noticed the camera is a bit wobbly as it moved through the sets, which is a bit distracting. Moving into the more fantasy setting, the designs of the creatures reminds me very much of something out of The Neverending Story or Labyrinth, which makes me wonder if they inspired some of the decisions at any point. Lilac Ball has a bit of a dark edge like the aforementioned films, with a trio of comic relief characters being cannibals, and this rather disturbing death scene of this giant bird thing that we follow for about five minutes before it is killed on screen and we are left looking at it’s dying breath. Very odd. Some of the creatures aren’t quite as imaginative as in the novels, probably due to technical and budgetary constraints. Gromozeka is a humanoid-looking alien with four arms for example, but in the original novels, he was much more alien looking, with seven eyes and such. A 2009 partial-remake of this film that, due to it being animated, was able to be much more creative with it’s designs (it even had Alisa’s actress from this film returning to voice Alisa’s mother, which is nice).

Overall, Lilac Ball is an odd combination of science-fiction and fantasy that isn’t really a combination: the film is evenly split between the two. trying to fit these two genres, and a full novel’s worth of plot into such a short runtime creates a story that can be difficult to follow. The film constantly feels like it’s being constrained by one thing or another, but there’s plenty of things going on to keep it entertaining for children, it’s just a shame there’s not enough time or space given to appreciate them.

-

#496 – Captain Nemo (1975)

Captain Nemo (1975)

Film review #496

Director: Vasili Levin

Just when you think you’ve reviewed every adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea…

SYNOPSIS: Following sightings of a mysterious giant creature in the oceans targeting various ships, Professor Pierre Arronax takes a voyage on the Blue Star liner to hopefully encounter and figure out the nature of this supposed beast. However, when the ship encounters it, an attack knocks the Professor, his servant Conseil, and harpooner Ned Land overboard. They awake and find that the sea monster is not a monster at all, but a submarine called the Nautilus, within which they are now captive under the supervision of Captain Nemo…

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Captain Nemo is a 1975 three-part TV movie, and an adaptation of Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. The plot of the film follows the original novel fairly closely, with Professor Arronax, his manservant Conseil, and harpooner Ned Land being swept overboard from the ship they are on to find themselves rescued by Captain Nemo and his submarine the Nautilus. Thus starts a series of adventures as the captives explore with Nemo the oceans of the world and it’s inhabitants. With a runtime of nearly three and a half hours, the film takes its time in establishing the setting and characters, and bringing the novel to life. It does omit some of the more fantastical (exploring Atlantis etc.) parts of the story and instead keeps it grounded, which a lot of the adaptations do admittedly, so that’s nothing special. With such a long runtime, the film does feel a bit too grounded, and there’s a lack of variety as the captives are confined to the Nautilus apart from the odd excursion under the sea. As such, the adventure aspect falls a little flat. The film does go into a bit more detail regarding Nemo’s past and the suffering of his family and people by colonial forces. The original novel kept things fairly ambiguous regarding the nationality of the forces, but the film here identifies them as British; which would have been accurate, since Nemo is meant to have been a prince in India, and it was British forces which occupied it. The film also casts a similarly critical eye on the Spanish conquest of the Incans. I suppose since the film was made in the Soviet Union they were more inclined to explicitly show the cruelty of Western colonialism and name the specific nations involved.

The characters from the novel are all faithfully represented, and the movie doesn’t really change their personalities, and neither does it need to: Arronax is the astute, analytical scholar, his manservant Conseil serves as a bit of comic relief (although it is much more muted and slight compared to other versions which make it more explicit), and Ned Land is the brawly, short-tempered type who directly contrasts with the rational Arronax and the stoic Nemo. The characters are portrayed very well with regards to their strengths, but they do again feel a little too grounded and as such never evolve past their starting points. Like the novel, and many of Jules Verne’s stories, there’s a noticed lack of any female characters; the only one being Arronax’s wife, who we see sparingly as she receives news about the fate of her missing husband.

The settings of the film are nicely varied: the flashbacks set in India and France feel authentic and lively. The Nautilus sets are very detailed and full of activity, although you see so much of them you might think you’re being held captive on the Nautilus too. The diving suits used for the ocean walk scenes look suspiciously like space suits, which makes me think they’re leftover props from a sci-fi film (probably one I’ve reviewed at some point). The underwater footage is a combination of stock footage and an indoor pool dressed as the ocean, which still looks pretty decent.

Overall, Captain Nemo is a fairly decent adaptation of the popular novel, and although it offers an accurate representation of the characters and settings, it lacks a spirit of adventure and the more fantastical elements that are a crucial part of the stories success. There’s obviously plenty of effort and care that has been put in to making this version, and it’s fairly solid. If you want a more streamlined cinematic experience though, you might be better off with another version (there’s plenty of them).

-

#495 – Aerograd (1935)

Aerograd (1935)

Film review #495

Director: Aleksandr Dovzhenko

SYNOPSIS: In eastern Siberia, a remote village is under threat from Japanese invasion, as well as the Soviet army planning to build Aerograd, a city of the future in the area. Stepan Glushak, a resident of the village and renowned soldier, must embark on a mission to protect his village.

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Aerograd (Also called Frontier) is a 1935 soviet film. The film centres around a remote village in Eastern Siberia, which is caught in between Japanese invaders, and the building of a new modern town called Aerograd under construction by the soviet army. Stepan Glushak, who was born in the village, returns to tell them of the new town, but is met with resistance by the superstitious locals, who fear change. The plot of the film is pretty threadbare: as with most soviet films from the time, this is nearly all just propaganda. There are numerous, extended speeches glorifying the red army, and songs singing its praises to the footage of fleet of soviet aircraft. Stepan tries to convince the residents of the village not to fear the soviet union, but they are sceptical, God-fearing people who fear change. It’s a simple premise, but one you can easily understand, and offers a solid base to sing the praises of the red army as they take out the invading Japanese forces.

The characters are fairly one-dimensional and uninspiring: Stepan embodies the soviet cause, and is the stoic, burly and heroic male lead. The residents of the village by contrast are portrayed as superstitious, irrational and old-fashioned in their fear of the red army. The Japanese, likewise, are overly-emotional and overacting to make them seen as different as possible. The Japanese soldiers are referred to as “Samurai,” even though they don’t have the traditional samurai armour or attire. I wonder if that’s a misconception that all Japanese soldiers are samurai that was held back then, but I can’t be sure. Either way, the purpose of the film definitely is not to accurately represent Japanese culture.

The cinematography of the film is perhaps it’s strongest point. There’s lots of expansive shots of the Siberian wilderness: a place that very few people would have seen on film or in person at that time. The cuts between cameras within scenes is also smooth and well done, particularly considering the scenes shot outdoors, and done when most scenes only consisted of a single camera. The footage also of fleet of airplanes, including being film from the planes themselves, is also quite well done. It’s difficult with these sorts of films to get to any kind of message the film has underneath all of it’s state-mandatory propaganda, and Aerograd is no exception. There’s some opinion that there’s some anti-Soviet sentiments that are hidden underneath the surface, but again, it is very difficult to make out. You could argue that the whole situation of Stepan abandoning his village for the glory of the Soviet Union paints him as a villain, and that certain moments of hesitancy regarding him killing his childhood friend open up a space within which things can be questioned by the viewer, but it is all very slight, and nothing concrete (but that would be by design, as any more obvious anti-Soviet sentiment would not have made it to film). It’s perhaps pretty easy to dismiss any Soviet Cinema as being simply propaganda, but there’s still plenty of decent films from the era that have a decent story etc., but I don’t think Aerograd is one of them.

-

#494 – The Apostate (1987)

The Apostate (1987)

Film review #494

Director: Valeri Rubinchik

SYNOPSIS: Miller, a physics professor, manages to create a device that can clone human beings. When the government learn of it, they want Miller to turn over the machine for their own uses. Miller also gets caught up in a conflict with his own clone, as the two lead similar, yet different lives, and come to different conclusions about what to do with their similar, yet different lives…

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: The Apostate is a 1987 science-fiction film based on the novel Five Presidents by Pavel Bagryak. The film opens up with Professor Miller, a physics professor at a university, visiting the President of a certain country: Miller has invented a method of cloning humans, and the government wants him to turn it over to them so they can use it for probably military purposes and such. The film revolves around Miller, as people try and get to him and his secrets, and also his clones, who lead the same, but different lives. The aim of the film is to explore the implications of cloning technology, and all the ethical conundrums that emerge from it. It’s all mostly stuff you’d expect to be explored, but it does it with a fair amount of depth and explanation. The structure of the film is a bit odd: almost self-contained scenes are separated by long interludes of imagery and music. As such, the flow of the story is rather disjointed and doesn’t really tie into a flowing narrative, which is odd seeing as it is based on a novel. The different scenes thus serve as dialogues about the various implications of cloning and the possibilities that come with it. As such, it becomes quite easy to get lost with regards to what is happening.

The aspect of the film which holds it together more than any other is the interactions between Miller and his clone: they both have the same memories, but their lives begin to diverge as they get involved with different people and such. Miller and his clone(s) are portrayed by the same actor, so the scenes involving them are carefully shot so that only one of them is completely visible at any one time. The fact that the two diverge in appearance (hair styles, glasses etc.) as the film goes on is also a nice touch that emphasises that divergence in their lives, and that while they may be identical, they are also now different. The rest of the cast doesn’t really stand out in any significant way, but I guess they don’t really need to. All of Miller’s clones moving about and some of them getting killed really does make the film even more confusing, but again the overarching plot doesn’t really seem to be the focus of the film.

With a runtime of nearly two and a half hours, the film takes it’s time in exploring it’s subject matter. The interluding scenes that bridge the dialogue scenes focus on vast landscape views, and often violent weather and associated destruction accompanied to classical music; which stirs up the feeling of nature responding to the cloning being itself a rebelling of nature, which is cool, but I’m not sure that’s the aim, and if it is it could have been done much more explicitly to good effect. As mentioned, the scenes where Miller and his clone are present are carefully shot so that the same actor can play both parts, and this is pretty well pulled off, and doesn’t feel forced. The rest of the cinematography too is pretty solid, from scenes that pan across large settings, to transitions between different parts of buildings, the camera work is fluid and competent. Overall, I don’t think The Apostate offers anything new to the discussion and implications of cloning, but it approaches the subject with clarity, while also plunging it’s depths too. The disjointed story does not lend itself to the traditional cinematic structure, and it’s very easy to get lost in the film’s wanderings. It’s probably not got anything unique enough to be worth a watch, unless you’re big into soviet cinema, and how it might take on the idea of cloning.

-

#474 – A Visitor to the Museum (1989)

A Visitor to the Museum (1989)

Film review #474

Director: Konstantin Lopushanky

SYNOPSIS: In a seemingly post-apocalyptic world, a man visits the shoreline from the city to visit a museum that is only accessible one week every year when the tide is low enough. He is following the rumour that somewhere inside is a portal to another world, where one can escape the hell that is the one he lives in has become…

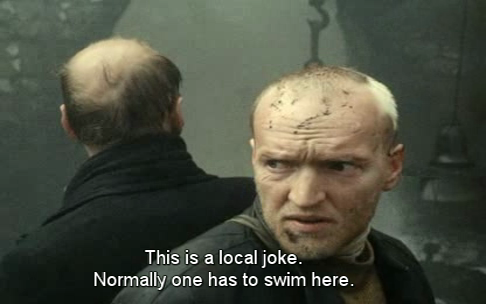

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: A Visitor to the Museum is a 1989 soviet post-apocalypse film directed by Konstantin Lopushanky. The film is set sometime after an unspecified ecological disaster has ravaged the planet: many people have become mutants and are locked up in reservations to be used as slave labour and such, while what remains of the unmutated live in cities. We aren’t given too much detail on the state of the world or what happened to it, but the backstory isn’t really important: like a lot of post-apocalypse films, how the world ended doesn’t mean much when you’re just trying to survive day-to-day in a new harsh world. A man visits the coast from the city hoping to visit a museum of relics from the old world buried beneath the sea. The path to the museum is accessible only once a year when the tides are low enough, and the man is following a rumour that within the museum is a portal to another world to escape the horrors of the one he currently lives in. The story of the film is very abstract and never hinges on definitives: a lot of the plot is casually explained as the man has tea with the family he is staying with, and they talk about the state of the world as very much matter-of-fact, in contrast to the true hell that the mutant “degenerates” are constantly experiencing.

Konstantin Lopushanky, the director of this film, worked on Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker film, and it definitely shows: the themes of isolation and desolation in a post-apocalyptic world and trying to find a way out are shared between the two, and there are very similar camera techniques and effects used to convey this. Lopushansky, however, always feels like Tarkovsky’s apprentice, and never really surpasses the master that is Tarkovsky, or offer anything different. The weak links in the film are definitely how the story reveals itself, and offers very little direction or clue to what is going on. Obviously, the film is meant to be ambiguous and centres around a loss of meaning in the post-apocalypse, but the film feels a bit too ambiguous in centring the main character and certain aspects of the film so you never know where they are or what’s going on. The plot points that do offer something include the contrast between the unmutated, who are unbothered atheists, and the God-fearing “degenerates” who scream out bible verses and quotes, even though none of them know what any of it means because the meaning of the bible has been lost.

The production of the film feels very considered, and again obviously taking inspiration from Tarkovsky. The outdoor location shots looks great, particularly the mountains of garbage and rubble that our protagonist traverses, which is apparently what most of the world looks like now. The landscape shots that emphasise the isolation of the protagonist abandoned amidst nature also works well. There’s also the large crowds of mutants in certain scenes give off an eerie feeling, as they move and act in seemingly genuine terror. Lopushansky uses the colour red to completely light many of the scenes, and it provides a good bit of consistency throughout.

This is definitely not a feel-good film: it is the end of the world, and we’re meant to feel it, the only hope of escape is this absurd rumour the protagonist is chasing about a portal to another world, which as the only option, shows just how bad things are, but again the unmutated just sitting around and discussing over tea as just a simple matter-of-fact furthers that strange contradiction. Overall, Visitor to a Museum definitely tries to capture some of that Tarkovsky magic of slow, epic films, but it never really hits the mark completely, nor does it offer anything new or original to the Tarkovsky formula. It’s not a bad film, and it received some decent recognition and awards, but again falls short of the master due to leaving things too ambiguous and without direction.

-

#459 – A Great Space Journey (1974)

A Great Space Journey (1974)

Film review #459

Director: Valentin Selivanov

SYNOPSIS: The All-Union Children’s Space Competition aims to find three children that will be the first youths in space aboard a new spaceship. Sveta, Sasha and Fedya are chosen from the one hundred thousand applicants to embark on the mission with the sole adult on board, Captain Egor Kalinovsky. After the ship is launched, Egor is found to be sick, and placed in quarantine, leaving the children in charge of the spaceship…

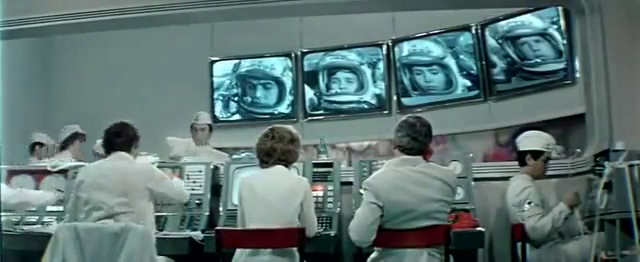

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: A Great Space Journey is a 1974 children’s science-fiction film based on the play The First Three, or the Year 2001 by Sergey Mikhailov. The film opens up introducing a space program that will choose three children to be the first young people in space. Out of one hundred thousand applicants from across the Soviet Union, three children are selected: Sveta Ishenova, Sasha Ivanenko, and Fedya Druzhinin. The three are sent into space on the spaceship Astra with the only adult on the voyage, Captain Egor Kalinovsky, who is in charge of the mission. When Egor is found to have a fever, that may spread to everyone else, he is placed in quarantine, leaving the children having to take charge of the ship and the mission. The story is fairly simple, being a film aimed at children, and is fairly light on the details concerning what the mission they are on actually is. Nevertheless, there is plenty that is going on in the film, as the children have to navigate through a fair amount of emergencies and strange situations as their journey continues. Not having an overarching objective hinders any sense of direction and accomplishment the film has, but nevertheless, there’s a good sense of adventure and enough variety to capture viewer’s imaginations. There’s a bit of a twist in the story that explains most things at the end, but I’ll discuss that at the end too.

The three main characters are the children that were chosen through the space program. Each of their characters are developed through flashbacks to when they were undergoing the testing, highlighting their relationships with their parents and each other. There’s also Egor, the only adult on the spaceship, who is placed in quarantine, but can still communicate to the others. One of the children, Fedya, is placed in command of the mission after Egor is quarantined, and it is hinted that he is troubled by something about the mission, but refuses to disclose it. Sasha is very animated, and teaches the other children dance moves to keep them entertained. Sveta is more headstrong and quick to rush into situations (contrasting with Fedya’s more reserved nature) and perhaps has some romantic feelings for Sasha. Between the three children, they have a good range of personalities, and at least one of them will appeal to children that the film was aimed at. Their interactions feel genuine in this extraordinary situation, and are generally likeable in their own way. There’s also a good balance between the children needing to act like adults, and also like children; such as when they complete their task running the spaceship, and immediately go get some ice cream from a nearby fridge.

The ending of the film reveals that the entire mission is actually just a simulation for the children to test their abilities. Fedya initially works it out, but keeps it secret for the remainder of the mission. You might think this is a bit underwhelming and disappointed that the children do not actually go into space…and in fact, that’s why actual soviet cosmonaut Alexey Leonov appears at the end of the film saying this exact thing. He also says that the time will come soon (?) when children will really go into space, and encourages children to continue looking forward to it and chasing their dreams, which is nice. The film also rewards the children for the completion of the simulation with a celebration and fanfare, so it still feels rewarding, and as if the characters accomplished something.

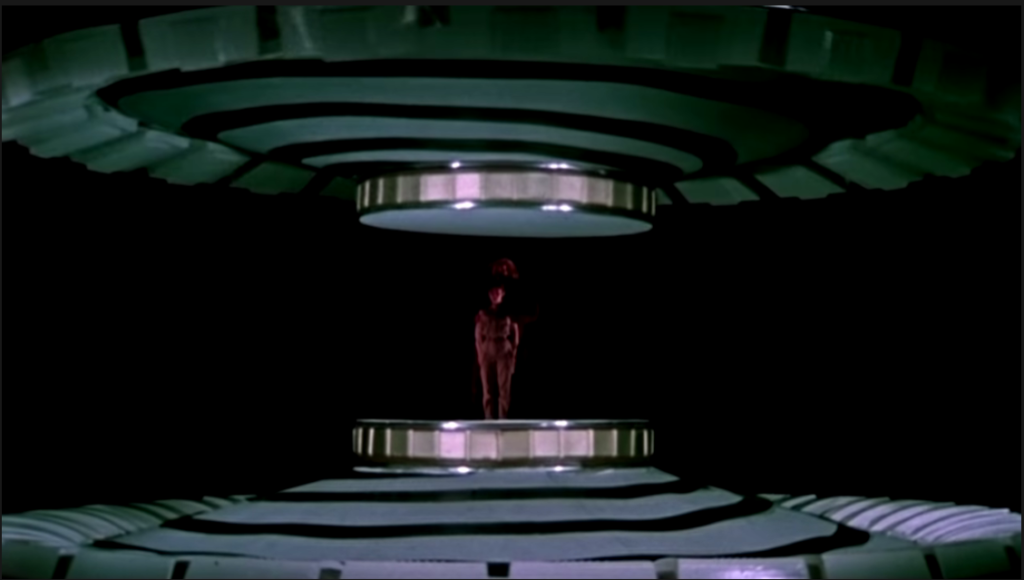

The quality of the sets and production values of the film certainly deserve some mention. The set of the spaceship is detailed, and the shots of the ship travelling through space are quite convincing given the time it was released. the model shots of the spaceship and other things also have quite a lot of detail in them. The whole aesthetic evokes the look of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which I’m sure is no coincidence. Given that the play the film is based on is called The First Three, or the Year 2001, it would certainly there’s a connection, but whether it is an homage, a parody, or knock-off, I’m not sure. The film was also apparently in production for two years, which I think shows in the look of the finished product. There’s also some musical interludes which don’t really fit in too well, but again probably something children would enjoy. Most notably, the song’s were written by a young Alexey Rybnikov, who would become one of the Soviet Union’s and subsequently Russia’s most famous composers, apparently in no small part due to the popularity of the soundtrack of this film.

Overall, A Great Space Journey is a fun little adventure that I’m sure its target audience would have enjoyed. The film is well constructed, and great effort had obviously been taken to make detailed and engaging sets. The characters themselves are relatable and distinct, without being too much of walking tropes, and the story has plenty of things going on in it, even if it lacks direction or purpose sometimes. It packs in a fair amount of detail and adventure in just over sixty minutes, and with some decent editing, always has something interesting going on.

-

#363 – Solaris (1968)

Solaris (1968)

Film review #363

Directors: Boris Nirenburg, Lidya Ishimbayeva

SYNOPSIS: Dr. Chris Kelvin has arrived on a space station orbiting the planet Solaris. When he arrives, he finds that his colleague is dead, and the two remaining crew are acting strange. Things get even stranger when his wife, who died ten years ago, seemingly appears on the station with no memory of what happened to her. He learns that people important to each of the crew appear to them, and this is somehow connected to the planet Solaris below them. Chris and the other crew must try to determine how these people have come to be on the station, and indeed if they are real…

THOUGHTS/ANALYSIS: Solaris is a 1968 TV film based on the novel of the same name. It is the first adaptation of the book, but the least well known, having been overshadowed by the 1972 Tarkovsky version, generally considered to be a masterpiece of cinema, and to a lesser extent the 2002 version, which saw widespread release. The film opens up with Chris Kelvin, an astronaut and scientist, docking his shuttle with the space station orbiting the planet Solaris. When he arrives, he finds a peculiar set of circumstances, with his old friend and colleague dead having apparently committed suicide, and the two remaining crewmembers being extremely vague as to what is happening on the station. The film’s plot unfolds slowly, with the mystery being slowly unravelled while new complications are constantly added. It is rather similar to the other two films versions, so I will assume it follows the plot of the novel with some accuracy. It’s slow-paced, but it fits the story well, since it gives the viewer space to reflect on the themes that the film is exploring.

Upon finding his wife, who died ten years ago, seemingly alive and well on the station, he realises that each crewmember has had someone personal appear to them. They suspect it has something to do with Solaris attempting to communicate with them, and somehow reaching into each of their subconscious’ and materialising a person within. This is one of the primary themes of the film, and the means of communicating with an entity or being that is completely unlike anything that could be encountered on Earth. It is explained decently, and explored primarily through Chris’ relationship with Harrie, or the facsimile that has been created, which leads to the distinction between the real and fake being increasingly blurred. It doesn’t have the style and depth of the Tarkovsky version, but this no-frills version still gets its message across. A lot of the film does focus on Chris and Harrie, and it seems like a lot of the science-fiction emphasis is sidelined in favour of the film being more of a drama. We never get to see the people ‘created’ for the other crewmembers or get any clue to who they are, so that leaves an odd mystery that will never be solved (in this version anyway). This further reinforces the main relationship between Chris and Harrie, again emphasising their drama more than the larger concepts of the film.

Even though this version doesn’t have the budget or vision of the Tarkovsky version, it still gets the story across well. Instead of elaborate sets and design, we see a rather sparse looking space station which instead emphasises a feeling of isolation, and gives the film a more horror-vibe at times. This is not a bad adaptation by any means: it delivers the story well, explains what’s going on clearly most of the time (there are some points, particularly near the end, that it gets a bit confusing), and explores its themes with a decent depth. However, given the 1972 Tarkovsky version is such a stellar adaptation and work of cinema, there is really not much value in watching this version, as everything in it is done so much better there. Overall, a decent adaptation, but completely eclipsed by its successor.

-

#24 – Stalker (1979)

Stalker (1979)

Director: Andrei Tarkovsky

Another science-fiction film directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, exploring the mysterious “Zone”…

In a home, we find a wife and child of The Stalker: A man who is hired by people to lead them through “The Zone”: A strange place where the laws of physics no longer apply. Within The Zone, there is a place called The Room, where people can go to get there one true wish fulfilled. The Stalker’s wife pleads with him not to go again to that dangerous place, but he ignores her pleas.

Stalker is hired by two men to escort them to The Zone. At a local bar, he meets the men, calling themselves “Professor” and “Writer”, who wish to find The Room and make their wish. The three set off through a military blockade that surrounds The Zone, avoiding patrols and gunfire, and finding a railcar to take them into The Zone itself…

The three arrive in The Zone, which resembles an overgrown area of countryside, with ruined debris scattered around. The lack of any sound gives it away that there is something not quite right about where they are. Stalker tells Professor and Writer to follow his instructions exactly, or they will be killed. He ties nuts/bolts to pieces of cloth, and throws them in the direction he works out is the best way to travel, to test out the safety of the route. The Writer is constantly skeptical of The Stalker’s odd actions, but The Professor generally follows his advice.

The two men have different reasons for visiting The Room. The Writer finds himself lacking in inspiration to write, and is hoping he can re-ignite his passions, while The Professor is hoping he can win the Nobel Prize. The Stalker mentions his mentor, Porcupine, who lead his Brother to death in The Zone, and wished for riches in The Room. However, a week later, he hung himself.

After travelling via a route of overgrown fields, underground tunnels and sand filled rooms, the three arrive outside The Room. There, a strangely placed phone begins to ring. the Writer answers and tells the person on the other end “This is not the clinic” and hangs up. Next, The Professor dials a number on the phone to brag to someone on the other end, and hangs up. The Stalker warns them both that The Room does not grant the wish they ask aloud, but it grants the true unconscious wish that resides deep within them. After this, the Professor reveals the real reason he came to The Room: He pulls out a bomb, saying that the power to grant wishes could be used for evil and terrible deeds, and because man should not have such power, needed to be destroyed. The three fight physically, and after a while, the Professor backs down from his plan, and the three sit down on the ground in defeat, none of them wishing to head into The Room and dare to have their wishes fulfilled…

Back in town, the three men are sitting in the bar where they first met. Stalker’s wife comes in and sees a dog that had got attached to Stalker and had followed him out of The Zone. Stalker then leaves the bar with his wife, the dog, and his child “Monkey”, who it was hinted at the start of the movie and now confirmed that she cannot walk on her legs without support (apparently she was born this way, and is a consequence of her father being a Stalker).

At home, Stalker’s wife tells him she has considered visiting The Room herself. Now, Stalker is having doubts about The Zone’s nature, and worries that her wishes would not be fulfilled. In a monologue to the camera, the Wife talks about whether she should leave Stalker, and the choices she has made by staying with him. She eventually re-confirms her commitment to him, while in the kitchen, Monkey sits at the table reciting a poem, she them apparently moves three glasses with the power of her mind (psychokinesis), and after the third glass falls to the floor, a train is heard going past the house, which causes it to shake…

A bit of background about this movie…this is another movie by Andrei Tarkovsky, most famously known for his 1972 movie Solaris. A lot of the production techniques used in that movie, such as long shots, steady camera motions, a slowly revealed plot, and a sparse and minimal soundtrack, were according to Tarkovsky himself much more refined in Stalker. Again, similar to Solaris, the movie is based on a novel, this one being Roadside Picnic by Boris and Arkady Strugatsky. The film deviates massively from the novel though, so much so that the only thing they really have in common are the terms “Stalker” and “Zone”. I think Tarkovsky took the novels concept as a base and applied his established style of filmmaking to it.

There is very little background and detail dedicated to the origins and mysteries of The Zone, why the military has surrounded it, and suchforth. Tarkovsky has expressed his dislike of western science-fiction, which focuses on flashy technology and quick changes in narratives and scenes. Stalker has a slowly revealed narrative that focuses on these three men as if they are the only people that matter. There discourse in some of the longer scenes reveals the impact of The Zone and it’s potential for the human race, and I think this is where Tarkovsky wants uis to focus our attention: On the conscious and unconscious aspects of human nature, and the insecurities and desires, both on the surface and deep within us, that makes us human.

Apparently, Tarkovsky went through 5000 metres of film while making this movie, and that isn’t a surprise when the movie has a runtime of over two and a half hours. Tarkovsky says with regards to the pacing at the beginning that “The film needs to be slower and duller at the start so that the viewers who walked into the wrong theatre have time to leave before the main action starts.” The fact that we have to wait nearly ten minutes into the film before we get the first bits of spoken daialogue is certainly proof of that. Also, I think Tarkovsky’s definition of “action” and ours is probably different, in a similar way to which our definition of science-fiction doesn’t perhaps match up to what happens in this film.

The world portrayed in Stalker is a ruined and desolate one, and it is easy to see why people would want to face the dangers of The Zone in order to get their wish granted. The world outside The Zone is filmed with a harsh sepia tone, and while one may instinctively associate sepia with nostalgia, here it is solely to highlight the grim and dull reality. When the film transistions to The Zone however, the world is in full colour, and the greens of the Eastern European countryside are revealed to us.

On a bit of a prophetic note; about seven years after making this film, the nuclear accident at Chernobyl occured, and the area which was affected by the radiation was officially called the “Zone of alienation”. It should be noted that the workers who are employed to work in the abandoned nuclear plant refer to themselves as “stalkers”, so clearly this movies image of empty and desolate wastelands found an equivilent in a real world disaster.

If you enjoyed Solaris and the cinematic techniques it employed, you will no doubt find Stalker of interest as well. However, if you have preconceptions about science-fiction being full of quick paced scenes, special effects and action, then perhaps this isn’t the movie for you. I think watching Solaris first is a good idea, since it somewhat bridges the gap between more traditional science-fiction and Tarkovsky’s own unique style of storytelling.